Sex and the Stratfordian

“Well it’s like Carrie and Mr Big, isn’t it?” she said, proffering a tissue.

“Is it?” I rather unhelpfully sneered.

My friend’s assessment of my recent break-up went down like a lead balloon, but at least it distracted me. I had always wondered how Sex and The City’s Carrie kept her friends, after writing about their love lives so explicitly, and often ungenerously, in her column. If I published weekly diatribes about the fact that Perdita* should not date men who use Nick Hornby novels as an excuse for their own inadequacies, or catalogues of Olivia’s* BDSM adventures, I’m pretty sure I would be several friends and a couple of relatives the poorer by the month’s end.

*Note that my immense fear of alienating anyone has lead me to use ludicrously Shakespearean pseudonyms. Any similarity to persons living or dead is purely coincidental!

As Carrie would say, “it got me to thinking”: what would Shakespeare have to say about about break-ups and relationships? Surely his oeuvre, a renowned encyclopaedia of human experience, would have something for me? If Carrie had kicked Mr Big for good in season 1 and decided to write a column about agriculture or pilates instead, she would have been sad for a while, but she would have “gotten” over it. Of course she would have had Gloria Gaynor and Crystal Gayle to help her on her way, but would she have found any Shakespearean gems to soothe her achey-breaky heart?

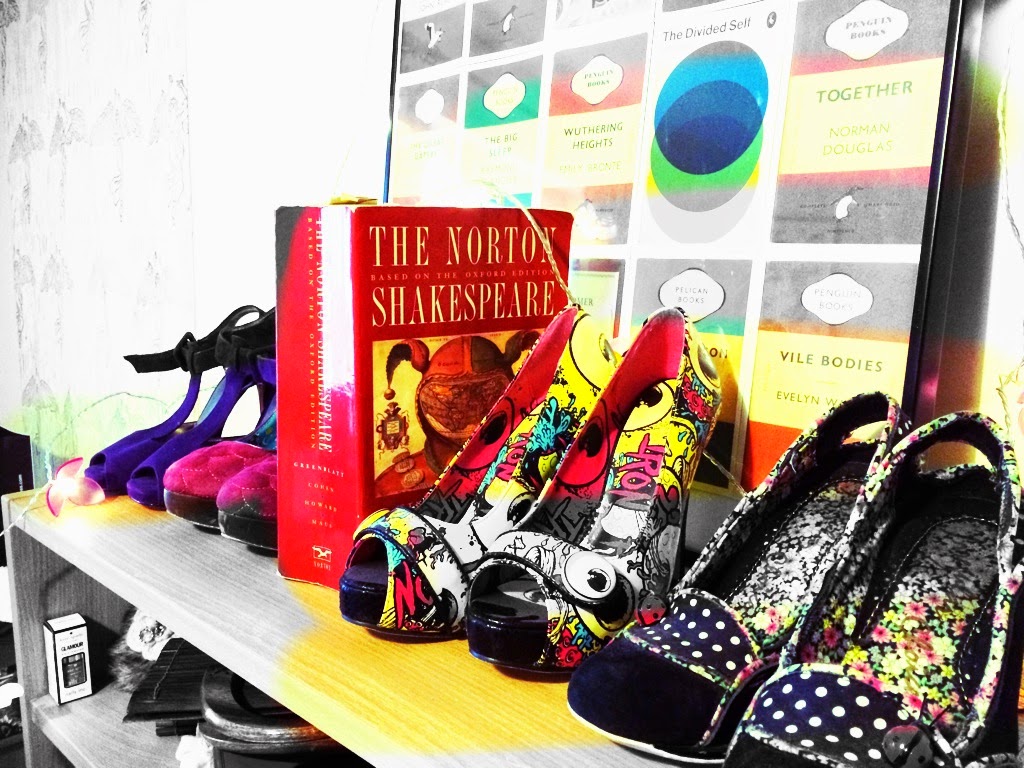

Despite being as full of sorrow and unrequited love as Carrie’s apartment is full of shoes, Shakespeare’s plays haven’t quite hit the spot (there’s a Samantha joke there but I’m not making it). A Shakespearean heroine ends up dead or married, and that’s really all there is to it. Sometimes they don’t even get to marry someone they either like or know! Think of Twelfth Night’s Olivia who ends up married to a total stranger. He may look like someone she fancies, but she doesn’t know him, and what’s more, he clearly has more of a thing for seamen (like Antonio). And what about poor Phebe in As You Like It? After quite categorically rejecting Silvius she ends up being hitched to him and told “sell when you can: you are not for all markets”. Need we mention Isabella from Measure for Measure who has placed her chastity above her brother’s life? She is neatly married off to the pervy Duke who pretended to be a friar in order to inveigle his way into spending out with her and Mariana. What would you be, apart from speechless? In Shakespeare, if you can’t get and keep Mr Big, or indeed Mr Small, or Mr Whoever else, death is really the only other option.

Hold on, before you plunge into despair, max out your credit card on Manolo Blahniks or eat entire tubs of ice cream in one sitting (I have to personally recommend Ben & Jerry’s Peanut Butter Cup for this purpose), there is hope on the horizon. The really, really good news is, you are not in one of Shakespeare’s plays! If you were Desdemona and your husband began to listen to the psychotic whisperings of his pal Iago, you could flipping well leave him and open an ironically named jewellery shop in Stratford-Upon-Avon. You wouldn’t have to stick around to be smothered in your own bed. If you were Helena, you might think to yourself, actually I don’t want to marry Demetrius. Afterall, Demetrius has treated you badly for a very long time, and there’s no rush to marry anyone at all. You could become a triathlete. When Ben and Jerry fail reading Shakspeare’s plays might make you rejoice that your lives are not governed by either comic or tragic plot conventions. So really, in so many ways, the loss of Mr Big is no ‘tragedy’ at all. I have so many choices and options. To quote Falstaff (out of context) “the world is mine oyster”, but sadly this is not the same story for every woman today.

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream Hermia is given a choice: either marry the man chosen by her father or die. Many women across the world and in the UK are the victims of forced marriage and if they resist, leave their husbands, or behave in any manner perceived to be shameful, they become victims of ‘honour’ crimes (abductions, acid attacks and other types of mutilation) and even killings. In 2011 the British police responded to a freedom of information request and revealed that they had records of 2823 honour crimes in that year, yet charities say that these reported crimes are by no means the whole story. Nazir Afzal of the Crown Prosecution Service informed the BBC that up to 12 British women a year would be the victim of an honour killing, while he estimated that up to 10000 forced marriages took place in the UK every year. For these women there really are no choices. They are trapped. In Much Ado About Nothing, when Hero is publicly shamed and accused at her wedding of adultery, her father, Leonato, wishes she was dead. “Do not live, Hero; do not ope thine eyes”. It is decided that the best thing for Hero and her family would be to pretend that Hero is indeed dead. While Leonato’s wish for his daughter’s death might seem extreme to many ears, for some that same response would be considered both natural and justified. Iqbal Khan’s 2012 production of Much Ado, starring Meera Syal and Amara Karan (both popular British stars), was set in modern day Dehli, yet much of what the director had to say rang as true for the UK as for India. The lavish and public performance of Hero’s wedding scene drew striking and painful parallels between what happens to Hero, a character created in the 17th Century, and 21st Century honour killings. Hero’s death is considered preferable to the idea that she has dishonoured her father. Much Ado is a comedy so Hero is not dead, and when her honour is proven, she is allowed to revive for a happy ending and marriage. In reality the dead do not come back to life. Productions like Iqbal Khan’s Much Ado use Shakespeare to talk about 21st Century problems, they raise awareness and can, hopefully, effect change.

Shakespeare’s play has its problems. Hero’s eventual marriage and forgiveness of Claudio suggests that had she been guilty then the responses of the princes and her father might have been justified. This is not the case. Honour crimes and killings are never justified. Women’s bodies are their own, and their sexuality and their loves are their own business. So despite the terrible film franchise that Sex and the City produced, I think I may settle down and watch an episode. As I roll my eyes at Carrie’s clichéd column, I’ll also be thanking my lucky stars that, although I think her attitude to credit cards is irresponsible, my life, with all its freedoms, is much closer to hers than it is to that of any Shakespearean heroine.

“Is it?” I rather unhelpfully sneered.

My friend’s assessment of my recent break-up went down like a lead balloon, but at least it distracted me. I had always wondered how Sex and The City’s Carrie kept her friends, after writing about their love lives so explicitly, and often ungenerously, in her column. If I published weekly diatribes about the fact that Perdita* should not date men who use Nick Hornby novels as an excuse for their own inadequacies, or catalogues of Olivia’s* BDSM adventures, I’m pretty sure I would be several friends and a couple of relatives the poorer by the month’s end.

*Note that my immense fear of alienating anyone has lead me to use ludicrously Shakespearean pseudonyms. Any similarity to persons living or dead is purely coincidental!

As Carrie would say, “it got me to thinking”: what would Shakespeare have to say about about break-ups and relationships? Surely his oeuvre, a renowned encyclopaedia of human experience, would have something for me? If Carrie had kicked Mr Big for good in season 1 and decided to write a column about agriculture or pilates instead, she would have been sad for a while, but she would have “gotten” over it. Of course she would have had Gloria Gaynor and Crystal Gayle to help her on her way, but would she have found any Shakespearean gems to soothe her achey-breaky heart?

Despite being as full of sorrow and unrequited love as Carrie’s apartment is full of shoes, Shakespeare’s plays haven’t quite hit the spot (there’s a Samantha joke there but I’m not making it). A Shakespearean heroine ends up dead or married, and that’s really all there is to it. Sometimes they don’t even get to marry someone they either like or know! Think of Twelfth Night’s Olivia who ends up married to a total stranger. He may look like someone she fancies, but she doesn’t know him, and what’s more, he clearly has more of a thing for seamen (like Antonio). And what about poor Phebe in As You Like It? After quite categorically rejecting Silvius she ends up being hitched to him and told “sell when you can: you are not for all markets”. Need we mention Isabella from Measure for Measure who has placed her chastity above her brother’s life? She is neatly married off to the pervy Duke who pretended to be a friar in order to inveigle his way into spending out with her and Mariana. What would you be, apart from speechless? In Shakespeare, if you can’t get and keep Mr Big, or indeed Mr Small, or Mr Whoever else, death is really the only other option.

Hold on, before you plunge into despair, max out your credit card on Manolo Blahniks or eat entire tubs of ice cream in one sitting (I have to personally recommend Ben & Jerry’s Peanut Butter Cup for this purpose), there is hope on the horizon. The really, really good news is, you are not in one of Shakespeare’s plays! If you were Desdemona and your husband began to listen to the psychotic whisperings of his pal Iago, you could flipping well leave him and open an ironically named jewellery shop in Stratford-Upon-Avon. You wouldn’t have to stick around to be smothered in your own bed. If you were Helena, you might think to yourself, actually I don’t want to marry Demetrius. Afterall, Demetrius has treated you badly for a very long time, and there’s no rush to marry anyone at all. You could become a triathlete. When Ben and Jerry fail reading Shakspeare’s plays might make you rejoice that your lives are not governed by either comic or tragic plot conventions. So really, in so many ways, the loss of Mr Big is no ‘tragedy’ at all. I have so many choices and options. To quote Falstaff (out of context) “the world is mine oyster”, but sadly this is not the same story for every woman today.

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream Hermia is given a choice: either marry the man chosen by her father or die. Many women across the world and in the UK are the victims of forced marriage and if they resist, leave their husbands, or behave in any manner perceived to be shameful, they become victims of ‘honour’ crimes (abductions, acid attacks and other types of mutilation) and even killings. In 2011 the British police responded to a freedom of information request and revealed that they had records of 2823 honour crimes in that year, yet charities say that these reported crimes are by no means the whole story. Nazir Afzal of the Crown Prosecution Service informed the BBC that up to 12 British women a year would be the victim of an honour killing, while he estimated that up to 10000 forced marriages took place in the UK every year. For these women there really are no choices. They are trapped. In Much Ado About Nothing, when Hero is publicly shamed and accused at her wedding of adultery, her father, Leonato, wishes she was dead. “Do not live, Hero; do not ope thine eyes”. It is decided that the best thing for Hero and her family would be to pretend that Hero is indeed dead. While Leonato’s wish for his daughter’s death might seem extreme to many ears, for some that same response would be considered both natural and justified. Iqbal Khan’s 2012 production of Much Ado, starring Meera Syal and Amara Karan (both popular British stars), was set in modern day Dehli, yet much of what the director had to say rang as true for the UK as for India. The lavish and public performance of Hero’s wedding scene drew striking and painful parallels between what happens to Hero, a character created in the 17th Century, and 21st Century honour killings. Hero’s death is considered preferable to the idea that she has dishonoured her father. Much Ado is a comedy so Hero is not dead, and when her honour is proven, she is allowed to revive for a happy ending and marriage. In reality the dead do not come back to life. Productions like Iqbal Khan’s Much Ado use Shakespeare to talk about 21st Century problems, they raise awareness and can, hopefully, effect change.

Shakespeare’s play has its problems. Hero’s eventual marriage and forgiveness of Claudio suggests that had she been guilty then the responses of the princes and her father might have been justified. This is not the case. Honour crimes and killings are never justified. Women’s bodies are their own, and their sexuality and their loves are their own business. So despite the terrible film franchise that Sex and the City produced, I think I may settle down and watch an episode. As I roll my eyes at Carrie’s clichéd column, I’ll also be thanking my lucky stars that, although I think her attitude to credit cards is irresponsible, my life, with all its freedoms, is much closer to hers than it is to that of any Shakespearean heroine.

Comments

Post a Comment